If you’re looking for a book about girlhood, then The Virgin Suicides probably isn’t the one for you.

Disguised as a story about just that, it tells far more about the obsessive, voyeuristic boys-turned-men that tell the story of the Lisbon girls’ tragedy. Everything told is through their distorted sense of reality, calling the mystery of the Lisbons even further into question. We see these girls as the boys saw them — through a festering lust. The mystery surrounding them is only ever amplified by their explanation.

The narrative choice of The Virgin Suicides is fascinating because it’s told from the point of view of this collective. There are one or two instances where the pronoun “I” is used but most frequently, the readers are told about a we. Within this, we do get clarification about the various boys and what some of them individually do in seeking proximity to the Lisbons. What is most interesting about this collective is that the girls they’re obsessed with are also mostly seen as just a collective. One would expect that that much fanatical attention would starkly paint each girls’ differences but that is not the case. Often they are seen as a single entity of their desire.

That being said, however, there is still some level of distinction between the sisters. We get some particular time with Cecilia in the beginning, the youngest of the sisters who’s suicide wreaks havoc on the family and suburban community as a whole. After her demise, attention gets shifted to Lux and one may wonder if it’s priming the reader to see a sequence of tragedy from youngest sister to oldest. However, as the story wears on, the most emphasis is put on Lux overwhelmingly, and this is not just because of her new position as the youngest living Lisbon.

Of the five girls, Lux gets the most attention because she is the one who fits most conveniently into the boys’ vision of what these girls are. She appears as a culmination of all of their sexual and cogitative desires, all the while just out of reach. Their desire for who they think she is spreads into all of the sisters and fulfills any holes where the girls don’t offer quite what the boys seek. I don’t think it’s without reason that we get the least discussion on Therese, the “brainy” sister who is passionate about nature and science more than she is coquettish as Lux is. Mild Bonnie has some instances that push her over further into the boys’ favor, and particular Mary’s obsession with beauty fits the bill, too, getting her a bit more time on the pages.

As we reach the conclusion, though, and see the boys’/men’s perspective of the girls evolve, it is still completely within the context that the girls do everything and make each decision to torment them. It is only through consciously peeling back their understanding of the situation that we could even begin to garner insight into the mystery still enshrouding the Lisbon girls.

The prose in this novel is dense and rambling, making it a little hard for me personally to get through for a bit. However, this incessance packs striking imagery. At time it’s ridiculous in its languished pretension but it all feeds into the novel. We see this tragedy–a true suburban gothic–through the lens of another tragedy in the fallacies of this collective’s obsession. Over and over, it’s posed, “Who are the Lisbon girls?” All the while, though, we’re pointed in the wrong direction for answers, angled away from the reality of the sisters and toward this voyeuristic delusion.

It’s the sickening marriage of the Lisbon sisters–sorrowful and snuffed–and their unprecedented audience–voracious and flagrant–that makes the drawl of this evocative novel harrowing. Still, we ask, “Who are the Lisbon girls?” And the answer is that it was never any of our business. In asking, we align ourselves with this hungry, thirsting group of boys/men. The monolith of the girls’ repressed inner and outer worlds, the dilapidation and decay encompassing their bloodline and coming of age and state of society beyond them was always theirs. Never the boys’. Never ours. I believe if the reader–as the narrator does–comes to a finite conclusion about the girls, they’re doing a disservice to the Lisbons and, ultimately, missing the point–which is that there is and never has been any real point to it at all.

Have you read The Virgin Suicides? Did you like it? Why, or why not? Do you agree with my assertions, or do you have a totally different idea/understanding? I’d love to hear your thoughts below!

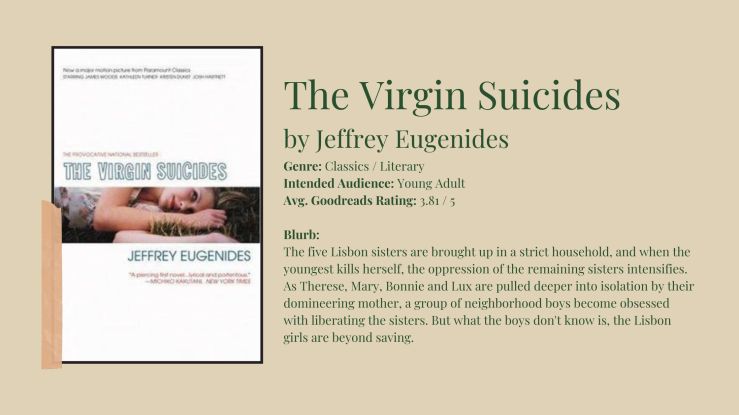

[…] 20. The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides […]

LikeLike

[…] The Virgin Suicides (Historical Fiction, Literary Fiction, Adult) […]

LikeLike

[…] a total sucker for interesting narrative takes (like the collective narrator in Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides, the unreliable narrations of Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, or any of the other epistolary […]

LikeLike

[…] that they’re based on, hence my picking up Fight Club and Girl, Interrupted (as well as The Virgin Suicides a few months back now). So far, I’m really enjoying these picks, even though they differ […]

LikeLike

[…] I’m not overly familiar with Jeffrey Eugenides’ writing style but since having read The Virgin Suicides this past winter, I get the sense that he’s somewhat renowned for his pillowy prose. Some people love it, some people hate it. For me, I enjoyed bits like this particular quote, straightforward but evocative. This book was a fascinating one, and in its controversial reception, I feel like it’s generally misconstrued, which I talked a bit about in my review of it. […]

LikeLike

[…] over the last few months was Emma Cline’s The Girls which in a lot of ways reminded me of The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides. It’s been lauded for its lavishing prose and imagery and relies on it heavily. It also has a […]

LikeLike

[…] this book if it’d be one of my favorites of 2025, I would’ve said no way. Similar to The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides, I didn’t think I really liked the book until I couldn’t stop talking about it for […]

LikeLike